We are unsure if true inclusive design can exist in the systems we operate in today, say curators of Design for All exhibition

The interview with curators of Design for All exhibition Thea Urdal and Herman Billet on universal design, creating meaningful connections and building communities.

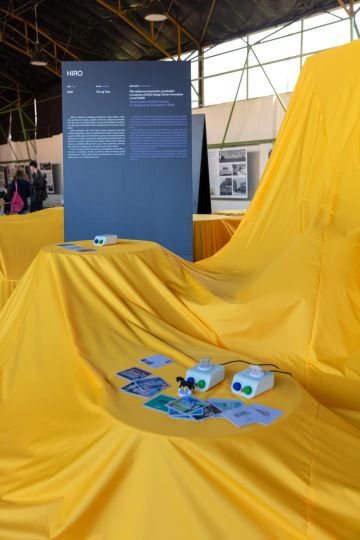

Herman Billet a Thea Urdal zajahují výstavu Design pro všechny, Foto: Zlin Design Week

There are many definitions of inclusive and universal design, I’m interested in your perspective – what does design, I’m interested in your perspective – what does it mean to you?

Thea: I am based at Nesodden, a green and rocky peninsula reached by ferry in the Oslo fjord archipelago. Here, I live in an oak forest with my family – alongside curious squirrels, tawny owls, mycorrhizal fungi networks and vast amounts of red-listed birds, as the land is part of a bird reservoir area.

We are currently caring for, mending and repairing a house from the 50s. As opposed to buying or building something new, we are making kin with more-than-human entities such as the black fungus living in the forest, gladly inhabiting the wood on our walls (and perhaps not so gladly for us, but symbiosis is not always cute).

So my way of approaching inclusive design is very much rooted in my praxis and everyday life, i.e. more-than-human care, thinking holistically about the entire ecosystem of an idea and a product, and how both human and more-than-human stakeholders will be affected and cared for in the future. It’s a way of being and designing with, so to speak, and a kind of mutual aid.

Herman: Generally, but perhaps more so with universal design, I tend to see the term from two standpoints. One is conceptual, and the other is angled towards accessibility. The latter has become more apparent for me after I finished my studies; how we struggle to universalise access to everyday things to the point where we can begin legislating the “do’s and don'ts” for designers, or any other profession.

The conceptual standpoint is broader, and is where I, and I think many other designers find energy. This is about how universal and inclusive design can be an entry point to explore undiscovered and overlooked areas of culture, society, everyday life, nature and beyond. Universality is then to recognise and include perspectives that can inform and challenge notions of what is normal.

Thea Urdal

Thea is a Norwegian journalist and also a designer. She curated the part of the exhibition dedicated to product inclusivity. She is interested in emotional design, curiosity, speculative fiction and the importance of semantics.

Herman Billet

Herman is a service design consultant at KnowIt in Oslo. As a curator, he has selected examples illustrating good practice in service design. He works with public and private entities on projects ranging from mobile devices to stadiums.

This year’s Zlin design week looks at it through the lenses of three different areas – space, product and lenses of three different areas – space, product and service design. Can you give us some examples of what service design. Can you give us some examples of what universal design means in each of these categories?universal design means in each of these categories?

Thea: I believe we live in such an entangled transdisciplinary world where space, product and service twist, fold and blend into each other, so to me it’s hard to make any precise separation. And it’s also unnecessary, I guess. Universal design is complex, but I have found that most things in life are indeed complex — there are webs of life everywhere, and we just have to embrace cross-pollination. Personally, I find that the most successful universal design projects are the ones where elements of biomimicry are involved, where there are clearly defined elite users, but at the same time, there’s still room for input, flexibility, fluidity and change in the iteration and testing phase. Rigidity is not a way forward in universal design, nor is it for the future at large.

Herman: Design to me is a very plastic term, not in that we only make things from PP, PE PET and other non-organic compounds, though sadly this is often the case. Plasticity means it’s shapeable, flexible and adaptable. I see the three terms as interconnected and in constant change with other categories today and to come. I think it’s important to always focus on how a product affects a space, how a service embodies products, or how a space is dependent on services. In each of the three, the universal design relies on their interdependence. Having an interdisciplinary focus is, to me, essential for designing an inclusive space, service or product.

Herman, one of your past projects focused on creat- ing connections between generations – a subject that ing connections between generations – a subject that can be seen far beyond space, product or service design. can be seen far beyond space, product or service design. How can designers contribute to solutions for these How can designers contribute to solutions for these kinds of challenges?kinds of challenges?

Herman: This is about the vantage points we can cho- ose as designers. We can either say that we’re designing a product, or that we’re designing for a specific mission, such as cultural change. Both vantage points can nurture change, but one is linked to a specific format and the other is open to several formats.

My work on intergenerational friendship was about perceptions of ageing. While ageing can often be seen through a health lens, it also has a massive cultural significance. We all have our own thoughts about what it’s like to grow old, and we’re constantly moving closer towards embodying our own perceptions as we age, known in social science as a “Self-Fulfilling Prophecy”. Growing old in Norway has a lot of negative associations to it, and I found that one of the best ways to nurture positive associations with ageing is through more friendship and connection across age groups.

This lens of exploring cultural and subcultural characteristics opens the design process to fresh and impactful ideas. Culture is embedded as “seeds” in the environments, actions and objects we use. Designing with a cultural lens is to redesign the seeds that can nurture value, and also to propose structures and connections, giving them fertile soil to grow. In the case of ageing, I approached this by designing the seeds that both the young and the old share, which was embedded in new spaces, services, products, methods and more.

"I am unsure if true inclusive design can exist in the systems we operate in today because someone will always get the much shorter end of the stick, even for companies operating with solid DEI policies"

How can we encourage or enforce principles of uni- versal design in our organizations or projects?versal design in our organizations or projects?

Thea: As we are still deeply entrenched in systems of neoliberalism and capitalism, I guess that depends on how we define organisations and projects — and if they are placed in the commercial landscape or in a more experimental field. Because there will always be these oxymoronic statements in design conferences such as “inclusive design = sustainable growth”. And the semantics there are so troubling and disheartening.

I am unsure if true inclusive design can exist in the systems we operate in today because someone will always get the much shorter end of the stick, even for companies operating with solid DEI policies. Most often it is the more-than-human world from which our raw materials derive from, as well as the manufacturers and labourers — predominantly situated in the Global South, producing goods predominantly for consumers in the Global North. I think there are many obvious reasons (some of which I’ve already outlined in my previous answers) for organisations to include inclusive design, but the main message from me is that it should be a key pillar in the operation, a foundation stone — not something that gets added into the mix because it will boost profit and look good on social media. It needs to come from within. It needs to be more than a financial incentive.

In order for that change to happen, we need to redefine words such as “innovation” to encompass modes of repair, mending and care. In sum, we need to start caring. That’s a monumental systemic shift. When this happens, the integration of inclusive design will not be a tool to be introduced, but a given.

Herman: We are increasingly seeing regulations and policies that designers can use to widen the scope of a project, though this isn’t extensive in every sector, while important but non-mandatory guidelines such as the UN’s Sustainability Goals can be a challenge to translate into concrete proposals.

Ideally, organisations should simply embrace the principles of universal design as the new standard, and the recognition of “Design Thinking” by even non-designers is a small hint in the direction that it is possible. While I see Design Thinking as lacking in that it can quickly be motivated only by economic interests, as well as simplifying the meaningfulness of the work that designers do, it also shows that designers can promote models that have a deeper impact on organisational ideals.

I think there is much more to learn from the innovative ways that designers approach the world. Organisations need more insight to gain trust in running broader strategic innovation processes with designers, while designers need more competence in working upstream (i.e. challenging and redesigning organisational frameworks, strategies and policies in parallel with designing end-products).

Sparking such a change can both be part of academia as well as piloting more radical projects to showcase the potential of new approaches. On the flip side, we may also need designers who take on a bigger “punk-mentality”; who dare to ask the often simple, but crucial “why-questions” that give organisations the chance to define progressive values that they can stand for and build on.

"Ideally, organisations should simply embrace the principles of universal design as the new standard, and the recognition of “Design Thinking” by even non-designers is a small hint in the direction that it is possible."

Thea, in your portfolio you describe your role as designer-as-translator. Can you explain what you mean designer-as-translator. Can you explain what you mean by that?by that?

Thea: As both a journalist and a designer I emphasise the importance of deep listening as well as inclusive language design. Simply put, I want my words and ideas to be understood by as many as possible. I need to acknowledge my stakeholders and design my language and visual output accordingly. This requires humility, vulnerability and a pedagogy of empathy.

I work with both text and textiles, two words that are etymologically related, both originating from the Latin “textus”, meaning “woven fabric, cloth, structure, framework”. To me, design is multifaceted. Design is prismatic: it has multiple sides and numerous colours. Design is an entangled, glorious mess. Design is many languages tied together, and I do not aim to be a polyglot, but merely a translator of sorts, moving between worlds, experimenting, documenting and communicating.

TUBU is a project by Thea Urdal and a collective of designers. It is a non-profit and part of the profits go to non-binary and women's health research. TUBU knitted garments were part of the Design for All exhibition in Zlín. Source: tubu.no

What is the one thing that every one of us can do to create more accessible and inclusive spaces, experi- to create more accessible and inclusive spaces, experi- ences and communities?ences and communities?

Thea: The world as we know it is spectacularly unfair, uneven and unjust, but fear is not compatible with action, and we need to employ a sense of joy and pleasure in our work, even in times of despair. In order to embrace modes of kinship in a time of any ecological collapse, fire or flood, we need to quite literally open up. We need to acknowledge privilege and design accordingly, listen, embrace skill-sharing, open sources and localism (as Zlín is doing in remarkable ways) — and embody a stance of “sharing is caring”. By doing this, I believe we can find modes of co-designing a livable future for all living organisms.

Herman: I don’t believe in evil, and I see the lack of inclusiveness as a lack of knowledge and empathy. To that end, we should nurture more knowledge about what inclusiveness means on a concrete level, and give people tools to act on behalf of everyone and everything. In that, we all need to acknowledge our own lack of knowledge and empathy and recognise the value of doing so. Embrace weirdness, seek the uncomfortable and cherish diversity. I want to end with a quote from the ironic, but beautiful song “Now That We Are All Different” by the Norwegian band DeLillos:

"Now that we are all different,

There are too many considerations to take,

But if we we were all the exact same,

We wouldn’t need much to feel fine,

Everyone would have the same needs,

Everyone would live in the exact same house,

No reason to be jealous,

Conversations would happen telepathically,

No need to cry or laugh,

And love would only cause problems."

The interview was published in Zlin Design Weeku 2023 Catalogue.

Articles

Design for All in pictures - Key activities of the project

Most of the activities of Design for All project culminated in May as part of 9th Zlin Design Week. Look back and remind the key activities such conference, exhibition and edu workshops through videos and pictures.

Recording from Zlin Design Week Conference is available

The Zlin Design Week Conference took place on 9 May 2023 in Zlin, Czech Republic and through lectures and joint discussions offered various perspectives on the topic of Universal Design. Watch the full conference recording or just select the talks you are interested.

Top 10 prejudices & preconceptions of inclusive design

There are many prejudices and misconceptions about Inclusive Design and Architecture. These are due to a lack of understanding or oversimplification. Following sentences reveal and counter some of the most common prejudices.